“Silence is compliance” is a phrase that many people toss off without thinking through how it works. People who use the phrase earnestly think that it’s obvious that silence in the face of injustice is equivalent to complicity in that injustice. But apparently, it’s not so obvious, because many people quote the phrase with a sense of irony, as though it is some kind of slogan for Orwellian thought control.

I have never seen the logic of “silence is compliance” thoroughly explained, so I’m going to attempt that here, just for kicks. I’m sure if I looked hard enough, I’d find a reasonably similar explanation, but the logic is straightforward enough that it’s probably easier to write it from scratch than it is to find an explanation as painfully dull as the one I’m going to give here.

First off, it’s important to discern that the phrase is only really meaningful in political contexts. People do sometimes use the phrase in other decisionmaking contexts, but in those it’s usually meant as a dumb joke. Somehow that dumbness is transferred through osmosis when some people see the phrase in political contexts. For example, when someone says, “Hey how about burritos for lunch? Silence is compliance!” – it’s obvious that this means nothing more than, “If you don’t say anything, I’ll move forward!” (And when you think about it, what even is illogical about that statement?) This is a completely different kind of claim than “Speak up about injustice! Silence is compliance!”

In a political context, it’s a reasonable moral claim, and deserves to be treated as such regardless of which side of the politics you’re on. We can demonstrate exactly why with an example of a controversial political issue … Hmmmm, so many to pick from, what to do, what to do … Well, though I’m tempted to go with old statues, or Confederate flags, or kneeling at anthems, virus names and nicknames, or “violent” protests, but no – these topics may be too hot right now, they could inflame consideration of the simple logic being offered. So I’m going to have to take down the temperature to … Islam vs the West. Truly extraordinary times we are in, that this qualifies as de-escalation!

Let’s start with a controversial statement about Islam, like “Islamic culture supports honor killings.” A “progressive” reaction to this might be something like, “that’s a horribly racist stereotype that is factually untrue.” A “conservative” reaction might be “we lose everything of value if we cannot acknowledge the truth of the harm done in the name of Islam.”

For comparison’s sake, let’s also present the caricatured responses from the land of social media:

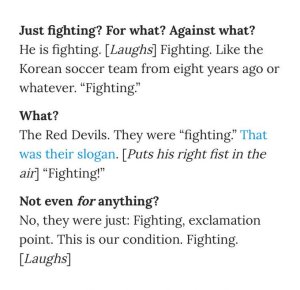

“Social Justice Warrior“: Your harmful words deny our reality as a people! Until you come to terms with the racism in your soul, you will never know the truth of your injustice! You must bow down in fear to our coercive power to silence your reasonable objections to our moral superiority!

“Intellectual Dark Web“: You’ve lost sight of the true meaning of liberalism, for you lack the courage to grasp the freedom that is clearly within your reach. You can never outlast the real truth that you are too weak to see. Intellect über alles!

Now, neither of these responses have anything to do with Islam or Western culture, and no one worth your attention ever says exactly these words. Nevertheless, the entire discussion proceeds in social media as if only the other side had said the words of their own caricature. It’s quite an amazing phenomenon.

Back here in the safe ol’ blogosphere, we have the space and the luxury of constructing arguments from steel rather than straw, and insisting that the only welcome comments are fires that temper the steel rather than burn the straw. Or something like that.

So, initial steelmen in this “Islam vs the West” example would be something like:

The “scholarly” view: An attentive reading of the Quran shows that honor killings are to be condemned, as an innocent life is lost and the perpetrators of this crime do not set a good example for society. Of course there are radicals; people with abhorrent beliefs and actions, but it is not fair to taint Islam with their distorted beliefs, just as it is not fair to taint all Christians with the beliefs and actions of the Crusades and many other wars and acts of genocide carried out in the name of a Christian God. It is unjust to impugn all of Islam by association with the horror of honor killings.

The “cultural” view: You can’t claim that a religion is just the words in a book. A religion is how people live it, and how it manifests in the world through the people who claim it, whatever the merits of their claim. I do absolutely condemn all of the wars and genocides of the Christian God, I do also agree that a Christian culture led to those evil outcomes, for the same reasons I cite regarding Islam. So when I say that Islamic culture supports honor killings, I am only stating a fair interpretation of facts and a cultural understanding applied equally across all cultures.

These may have weaknesses, but they are not strawmen, and they can both be much improved. It might even be possible to improve both of these positions to the point that they are not in factual conflict, while they still remain in support of their political positions – but that would be a difficult discussion. It would be lengthy, it would be nuanced, it would be challenging and at times frustrating and possibly emotionally exhausting.

The fact is, all serious political controversies have steelman arguments (including any controversy over whether I should be saying “steelwomxn” instead). But it’s much easier to burn down the strawmen than do the hard work of discussion.

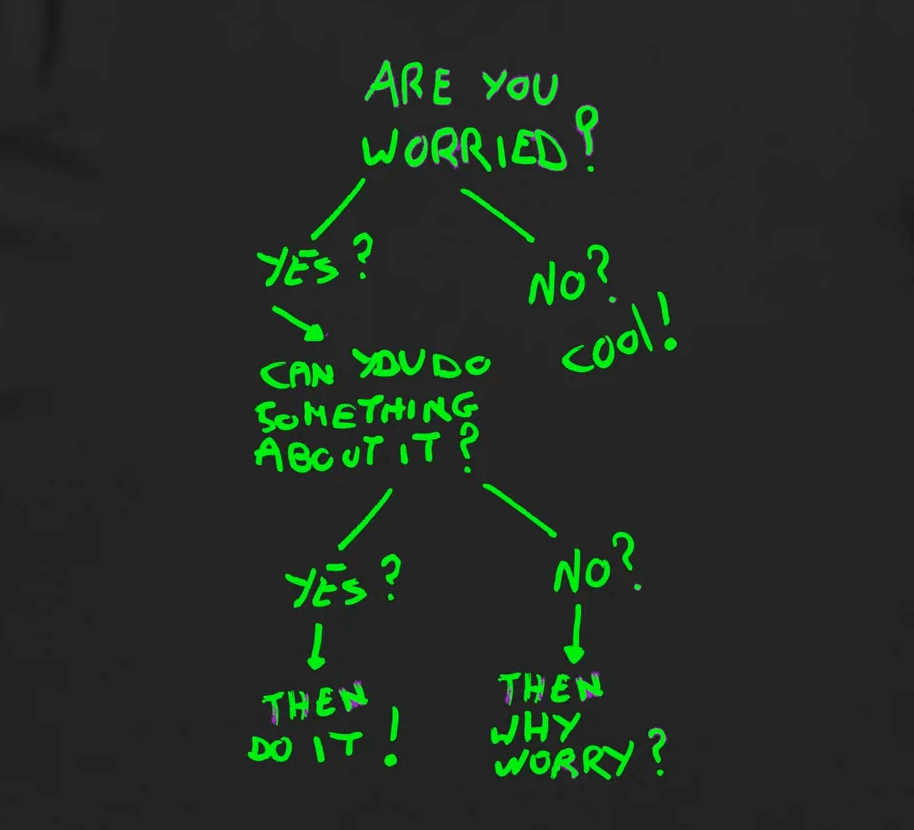

And further, it could be a reasonable moral choice to decline to do the work. In general, you are not obligated to provide anyone your intellectual or emotional labor, and you don’t even need to have a reason to decline, not even privately for yourself. You only have an obligation to engage with people that you’re already in a relationship with, like your partner, or your kids, or your neighbors, or your town, or your country … hey waitaminute …

Politics, of course, is an endeavor among people living in the same society, even if some of those people wish some of the others would leave. Any belief in a political solution raises the obligation of informed discourse. Maybe you don’t have to discuss every little political issue that the neighbors want to gossip about on Nextdoor. But you most certainly do have an obligation to participate in discussions of justice in your society, because if you are willingly living in an unjust society, then one way or another, you will eventually suffer the consequences if you aren’t already.

When a political issue raises questions of injustice, understanding that you have this basic civic obligation to participate is only the first step for making silence into compliance with the injustice, but let’s be clear: you can’t skip that step. To say, “I don’t owe anybody anything!” is simply to withdraw from political participation entirely. That may be your right in some circumstances, but if the current situation is indeed unjust, and you decline to consider yourself in the society at all – when it is in fact true that you are in the society – then your objection is based on a lie, and your silence is willing compliance with injustice.

But what if you do recognize the obvious fact that you’re in the society, but you just don’t want to say your opinion because you know that other people won’t like it? In this case, you are even worse, morally speaking, than in the prior case. There is a claim of injustice in your society, and you will not speak on it because you are afraid of what others will say? How is that a defense of your silence? What if you’re wrong, and your opponents are right about the claim – don’t you want to support justice even if you’re wrong? And even worse, what if you’re right, and your opponents are wrong about this claim of injustice – wouldn’t true justice be better served if you spoke up, regardless of what anyone says in response? In this case, silence is not only compliance, it is cowardly.

And what if pure intellectual freedom favors one outcome, while the demands of social justice favor another? Again: if either of these things actually matter to your society, and you remain silent, then you are compliant regarding the claim of injustice. Ok, one last shot: What if intellectual freedom allows anyone to favor either outcome, but only one of the outcomes supports injustice? Isn’t individual freedom the highest freedom of all? “I still want to pick the outcome that supports injustice, and the inviolable freedom of my mind gives me that right!” So … you’re saying that you could choose to believe either, and you consciously chose to believe the one that favors injustice, just because … you like it better? At this point, there is only one word for you, and I’m too polite to use it, motherfucker.

These intellectual gymnastics are unnecessary. Simply note that all claims of injustice perpetrated by the state are claims that the powerful committed injustice against the powerless. So the default outcome to a true claim of injustice by the state, if nothing is done, is for the injustice to continue. If the claim is false, and you don’t speak up about it, then you are contributing to the decline of a just state. Either way, the worst thing you can do is remain silent.

My point isn’t whether any of the stereotypes, caricatures, steelmen, strawmen, or painfully obvious statements above are bulletproof. My point is only that there is a reasonable and straightforward argument for why silence is compliance, and those who only view the statement mockingly are making a careless mistake. I’m not saying that everyone who utters the phrase has exactly this logic in mind, with this kind of specificity – good people usually don’t have to think it through in that much detail, because it doesn’t occur to them that anyone doesn’t see the clear logic: silence in the face of injustice is morally equivalent to compliance with that injustice.